I was four when me and my mother were walking home from our neighborhood hardware store on a warm San Fernando Valley morning. Our path crossed twelve blocks or so, a long ways for my little legs at the time. She was carrying a bottle of some sort, and I was following closely.

About halfway, the bottle slipped from her grip, fell to the sidewalk, and my next memory is of being under the tap in a stranger’s kitchen sink across the street. I fit entirely inside the sink, knees to chest. Then I was wrapped in a blanket on the sidewalk near our house waiting for the ambulance. I must have been wearing short sleeves and shorts because my collection of scars bloomed on my right knee and right arm as well as on my neck and face. My scar-face, as the boys in elementary school called me before I discovered the merciful magic of make-up.

Inside the bottle was a drain cleaner containing sulfuric acid, which can have a pH of less than one on a scale of 0-14. Interestingly, on the rainbow pH scale, number 14 is labeled as drain cleaner, so there are apparently different formulas. The idea is that the pH of drain cleaners is at the extreme ends of corrosive. To this day I avoid that particular aisle in all hardware stores. When I hear the word acid in any context, my scars twitch. I feel their shiny vulnerability and irretractable foreverness.

What I went through with acid is a trifle compared to what the ocean is going through with acid. I’m just one human compared to the trillions of sea creatures who have acid to contend with. My skin was dissolved in a dozen splashed spots, but their entire bodies are being dissolved.

Before my Oceanography lesson on ocean acidification, I admit I didn’t know much about it. I figured it was something bad happening somewhere in the ocean, but no one I knew talked about it, so how bad could it be?

Briefly, ocean acidification is the water’s change in pH due to an increase in carbon dioxide altering its chemistry. The ocean absorbs 25% of the CO2 we emit via coal, oil, natural gas, and since the industrial revolution, CO2 has spiked. When carbon dioxide dissolves in the ocean, it reacts chemically with the water molecules and forms carbonic acid, which then breaks apart into hydrogen ions and bicarbonate ions. This process releases hydrogen ions, and it’s these guys that determine pH level. A higher concentration of CO2 means more hydrogen ions breaking loose, which means higher acidity as well as less carbonate ions, which are a necessary component for the growth of seashells. This PBS video is a great animation of how ocean acidification affects all kinds of things in the sea.

There’s been a 30% increase in hydrogen ions in the ocean over the past 250 years. The speed of acidification is occurring ten times faster than in the past 50 million years. It’s happening too abruptly for most species to evolve fast enough to survive. Same as with climate change.

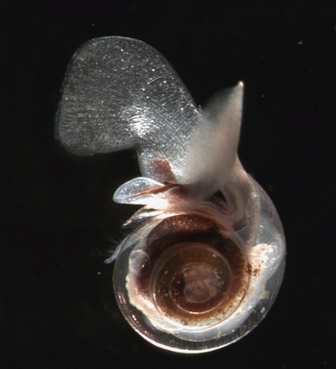

Less carbonate in the ocean means that animals with shells have less available to them to bind with calcium to grow their calcium carbonate shells. This prevents the shells from growing properly, if at all. So oysters, clams, crab, mussels, and other bivalves struggle to survive, especially as babies.

And when the tiniest organisms near the bottom of the food chain disappear, like the pteropod (sea butterfly), that loss travels up the food chain to salmon, orcas, whales, shrimp, even birds.

When these essential creatures disappear, humans will still be able to survive by growing food on land. But whales, sharks, skates, fish, and everything else in the ocean don’t have the choice of a chicken sandwich.

In the Puget Sound, 30% of marine life (about 600 species) need carbonate ions to grow their shells, so our region may feel the effects of acidification more quickly than other places. A decade ago oyster farmers in the Pacific Northwest found that their baby oysters weren’t surviving in their hatchery. In consulting with scientists they discovered that it wasn’t due to disease, as they originally thought, but rather the oysters were struggling when the pH got low, hindering their growth.

Shellfish aren’t the only ones affected. Higher CO2 levels can muddle with a fish’s brain by messing with their GABA receptors, causing the fish to behave strangely, like swim toward a predator instead of away. More acidic water also has the effect of transforming coral reefs from vibrant, biodiverse ecosystems to dull, slimy, and mostly dead zones. Coral reefs sustain 25% of marine life, so this isn’t ideal.

A species may be able to handle one stressor, but not multiple. Kind of like us. If our day job is stressful and exhausting, but our home is peaceful and restful, we can find a work-life balance and thrive. But if more stressors are added, maybe a sick child or aging parent or challenging marriage, those stressors will start to compound, and we’ll start to fall apart both physically and mentally.

At the moment, we’re throwing all kinds of stressors at the ocean – acidification, climate change, marine heat waves, overfishing and bycatch, oil spills, pollution, plastic. Life in the ocean can only handle so much before being forced to give up.

Aside from fishermen losing businesses and people losing their seafood sources, there are millions of species who have evolved tens of millions of years only to have us allow them to disappear.

It’s too late to stop climate change, as we’re passing temperature goals set years ago, but we don’t have to totally boil the planet. We can slow down the change by more quickly transitioning away from fossil fuels in all its forms, including plastic. At the same time, it’s all hands on deck to try to save the species able to survive the coming decades. They need our help.

Writing this post gave me the urge to support our local oyster farmers, those on the front lines of acidification. I’ve always loved oysters, but they are a rare luxury. I asked the fishmonger at the grocery store what he knew about the health of oyster farms in our area. The hama hamas available in the case were from a farm in Hood Canal about two hours away. My inquiry caused some confusion, as he thought I was concerned about shellfish poisoning for my own sake. After more rambling on my part, I realized a discussion about the science of ocean acidification is probably best done away from the seafood counter when others are waiting their turn. A field trip to Hood Canal will be planned.

At home we concocted a sauvignon blanc mignonette to accompany our oysters. I communed with my hama hamas, allowing the soft briny bundle to dissolve on my tongue in sparkling, seaful, soulful spirituality. I thought of all the others in the ocean who can’t see the future like we can. They are innocent. I was innocent as a four year old too, but I’m grown now, and the responsibility to protect the innocents has shifted to me.